The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley

The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley

Edited by Rod Smith, Peter Baker, and Kaplan Harris

University of California Press

512 pages

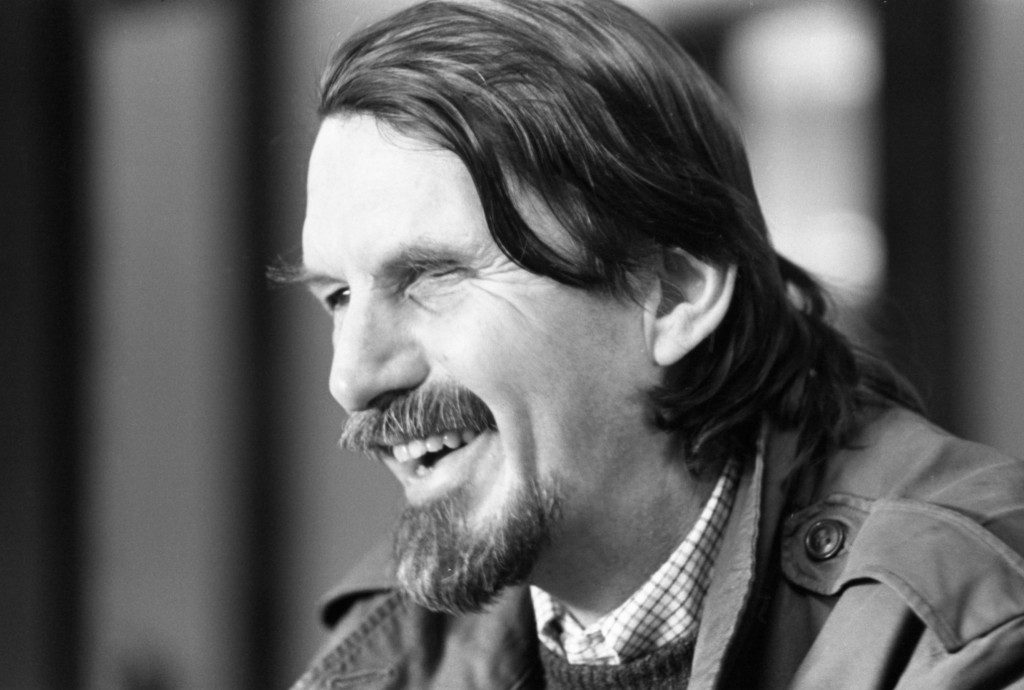

What emerges immediately from The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley, a newly edited volume of Creeley’s correspondence from 1945 to 2005, is how little time one of the most formative voices of post-war American poetry actually spent in America.

Creeley, a prime mover of the period, was responsible — as a poet, editor and publisher — not only for writing some of the most important poetry to emerge in the decades after World War II, but for fostering the publication of new poetry, and formulating theories about it. What is perhaps more impressive than his significant effect on American poetry is the fact that his influence came primarily through correspondence.

Born in Arlington, Massachusetts in 1926, Creeley served in the American Field Service in India and Burma during World War II, then attended Harvard, but left without a degree. He soon moved with his wife and son to a farm in New Hampshire, where he bred pigeons. Then things got very interesting. First he moved nearby to Aix-en-Provence in 1951, then to Majorca the following year. After a stint at Black Mountain College and a divorce, he moved to Guatemala. Then to New Mexico. Then to British Columbia. Then Buffalo, New Mexico, and San Francisco, before finally settling into a teaching position back in Buffalo. His last locale was Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Both a lack of settled comfort and a dedication to seeking the unknown, or moving “onward!” as Creeley refrains throughout these letters, is perhaps a key to Creeley’s commitment to writing, in fiction, poetry, expository prose, and letters. As he writes in 1952: “my place is so much on the paper, and not where it might, even ought, to be. I’m real portable these days, like the fucking typewriter. I argue against ‘place’, and that false sense of what it counts as, which is usually generator for an altogether dead memory, etc.”

Throughout Creeley’s travels, he maintained a vigorous involvement with avant garde American poetry. The 1950s alone account for nearly 40 percent of the letters here, as the editors point out. For much of that decade, Creeley and Charles Olson were nearly fanatical correspondents, sharing poetry and ideas, arranging the publication of books on Creeley’s The Divers Press in Majorca, or in The Black Mountain Review, which Creeley edited.

These letters provide insight into Creeley’s work and illuminate the generation of ideas that have come to be synonymous with contemporary poetry. By placing these concepts in the context of Creeley’s life, and in the context of the letters in which they were composed, The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley expands our understanding of the sharp subtlety of Creeley’s thought. Perhaps his most famous dictum, “form is never more than an extension of content,” which Charles Olson cited in his watershed essay “Projective Verse” (1950), is here presented in its entirety:

That is: the intelligence that had touted Auden as being a technical wonder, etc. Lacking all grip on the worn & useless character of his essence: thought. An attitude that puts weight, first: on form/ more than to say: what you have above: will never get to: content. Never in god’s world. Anyhow, form has now become so useless a term/ that I blush to use it. I wd imply a little of Stevens’ use (the things created in a poem and existing there… & too, go over into: the possible casts or methods for a way into/ a ‘subject’: to make it clear: that form is never more than an extension of content. An enacted or possible ‘stasis’ for thought. Means to.

The editors have done a fine job creating a selection of letters that forms a narrative with enough non-sequiturs and varied correspondents that the book never lulls. Their scholarly apparatus is streamlined yet informative. The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley is thrilling, emotionally and intellectually. From the crowded warmth and occasional despair of Creeley’s home life to the vibrant exactitude of his thought, these letters charm, challenge and inspire.

Throughout his mobile life, Robert Creeley maintained a single-minded dedication to poetry and the unique difficulties of putting into language the creative rhythms of conscious thought. Despite his international peregrinations, he remained a New Englander until the end. As he wrote in 1976 referring to himself, “New Englanders don’t need anything, they just want it all.”

–Stephan Delbos