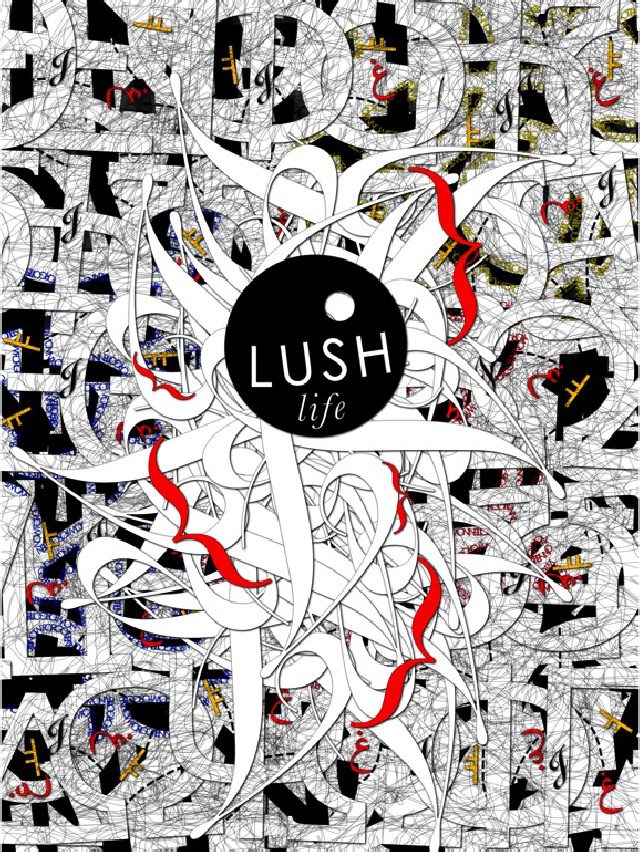

Editor’s Note: Nico Vassilakis, a recent replant to NYC, is a poet working in both the textual and visual alphabet. He co-edited The Last Vispo Anthology: Visual Poetry 1998-2008 (Fantagraphics Books). (Read the review from B O D Y here). You can see more of his intriguing work at Elective Affinities; Brooklyn Rail; eratio eidetics; and here. His latest book, ALL-PURPOSE Vispo, was published in January. He talked to us by email about the history and future of this hybrid genre of literary art.

B O D Y: What does visual poetry have to show or teach us in the 21st century?

Nico Vassilakis: Vispo is clearly a response to language. It tends to enhance the quantum aspects of language by focusing on the elemental design parts of language material. What’s that mean? People like fidgeting with alphabet.

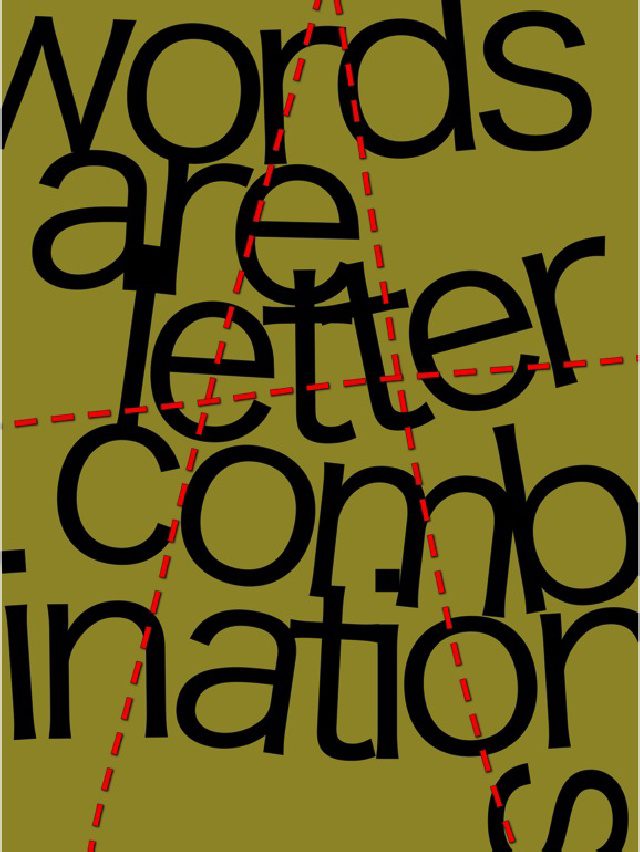

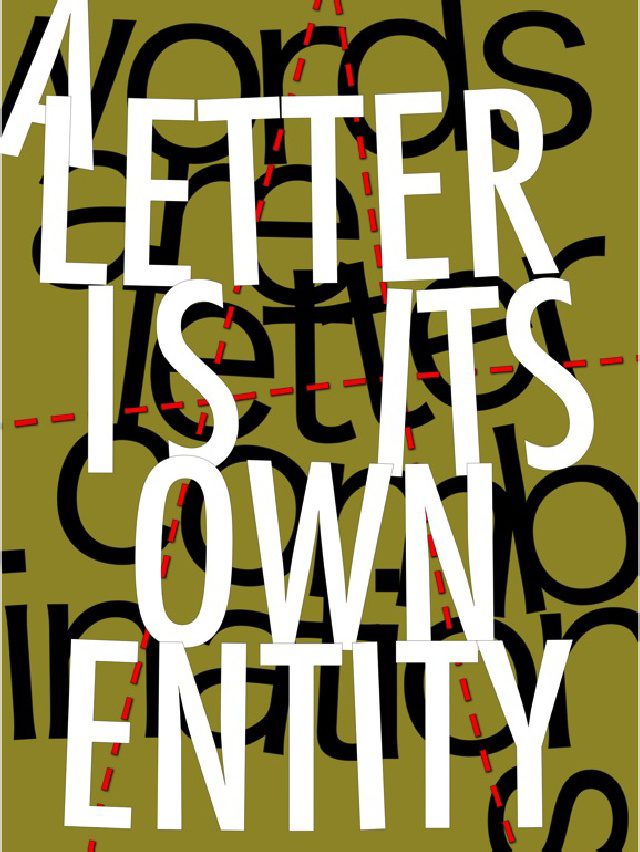

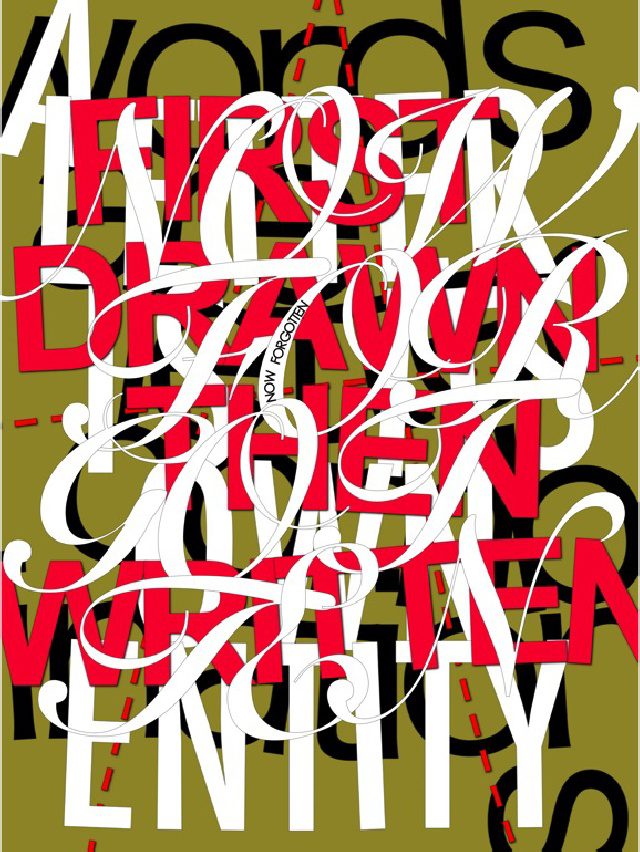

The letter, itself, has been my point of interest.

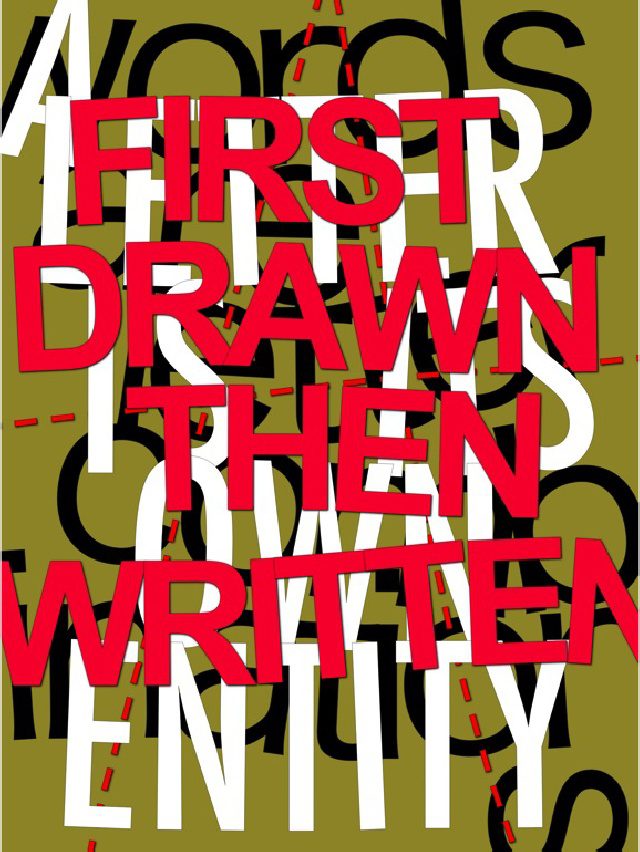

Vispo is a response to reading and writing language. There is a connection between seeing writing and writing reading and reading seeing (hand-eye-brain).

Though language is used as the common platform for communication, it’s prone to being creatively finessed in any number of ways. One of these is visually. Vispoets transmogrify, they undo the word, they reveal the potential locked in the word by visually deconstructing it. They replace language with other visual language.

In this millennium it’ll be about alphabet and machine.

B O D Y: You recently co-edited, with Crag Hill, The Last Vispo Anthology, which has a rather interesting title. Can you talk about the scope of the book, your aims for it, and where you see the movement going from here?

Nico Vassilakis: The anthology is meant to be a snapshot of the years 1998-2008 and a peek into how digitalization affected visual poetry. The aim is to make this type of work available to wider audiences. The movement is flourishing, yes, but inside a bubble. Social media helps to spread vispo, but it gets caught in its own categories, its own groups, and has trouble spilling over into other forums, other places. Vispo is Poetry’s bastard child, a figment of language’s imagination. Yet, more and more work is creating a critical mass that will need critics, presses, pedagogic direction and support. Because of computerization, with its ease of sending work, the movement, I call it fascination, has grown exponentially. It’s healthy, doing great, but suffers from growing pains.

B O D Y: Where do you see yourself going from here, as a practitioner and editor of visual poetry?

Nico Vassilakis: My fascination with how letters sit beside each other and patiently wait to be freed of their word logic scrum hasn’t subsided. So, I capture that alphabetic dalliance as document of some future language event. Editing wise, a project that would intrigue is to compile mini vispo anthologies from countries around the globe.

B O D Y: Why Visual Poetry? Why not visual art, or poetry? That is, why are artists/writers drawn to creating visual poetry, and what aesthetic function do you see it serving in the landscape of contemporary art and literature?

Nico Vassilakis: Vispo is a byproduct of ones experience with literature, with writing, reading and seeing. It is not an art movement, but imagine someone might say differently.

B O D Y: For someone unfamiliar with this kind of work, how would you instruct them to read/view it?

Nico Vassilakis: To me, encountering visual language is a curiosity, is a matter of staring through markings we’re accustomed to semantically, syntactically, and getting to another other side. It’s about how you look and read your way passed words and refamiliarize yourself with the intentional drawing of letters. From there it is seeped in the subjective exchange a vispoet has with language and what language means to them.

B O D Y: Much post-modern poetry is predicated on the idea of the poem being an event in language. This isn’t necessarily the case with a visual poem. So, what, in your mind, is a visual poem, and how does it have an effect on the reader/viewer?

Nico Vassilakis: I might misunderstand you here, but a vispoem is certainly an event in language. It uses the same material, it creates a charged environment and conveys a moment in time. A modern vispoem is a response to language, an outburst that challenges what language is and how it effects us.

B O D Y: Some people might think visual poetry is a free-for-all. Is it? Can you talk a bit about its history?

Nico Vassilakis: There are those who have spent time documenting all intentional markings, both historic and pre-historic, in order to create ancestral ties to vispo (See here). Vispo, and vispoets, is an unorganized, not disorganized, bunch. Like all groups, there is a struggle to define itself as so many have different ideas of what it is and what it means.

B O D Y: How has digital technology affected visual poetry, and do you think that effect has been positive or negative? I’m thinking especially of Apollinaire’s Calligrammes, for example, which are essentially “creative typography,” versus some of the more contemporary digital work you feature in the anthology.

Nico Vassilakis: The obvious answer is, yes, positively. The computer, be it hand held or on your lap, has changed everything about visual poetry. Not only can you create works with ease and in a fraction of the time, but sending it out to others is reduced to seconds. This is not to say that hand crafted work has gone out of favor. It hasn’t, but even that can be scanned in a minute and sent out to friends. Apollinaire’s Calligrammes seem to be a predecessor to vispo digitalization and not in conflict. The Calligrammes are in tune more with the concrete poetry era, where the reduction of words was paramount. Visual poetry has diverted from this, in my mind, toward the letter not relying on its word host.

B O D Y: Is the book the best medium to convey digital poetry? If not, what is? And, how has/will visual poetry be affected by the decline of print culture?

Nico Vassilakis: The book, as a thing, cannot be surpassed, but with all the programs out there to disseminate content, the book is/has becoming/become obsolete and fetishized.

Vispo can be seen, read, written or drawn in nearly any medium. Vispo has had very little print love over the decades. Very few presses have lent their hand to the cause, but hope is there that something will break, that kids will be encouraged to vispo in school and second guess the word logic messages that surround them.

–Interviewed by Stephan Delbos