Nazim Hikmet:

The Life & Times of Turkey’s World Poet

By Mutlu Konuk Blasing

294 pages

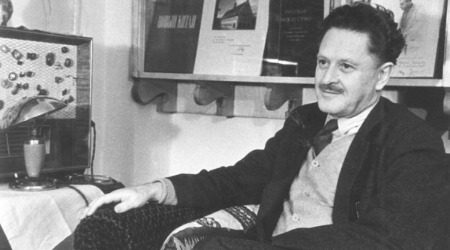

Mutlu Konuk Blasing is America’s leading scholar of the legendary Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet (1902 — 1963), having co-translated Poems of Nazim Hikmet, the epic poem Human Landscapes from My Country, and Hikmet’s autobiographical novel Life’s Good, Brother. As such, she is to thank, with her co-translator, the poet Randy Blasing, for bringing this irascible, joyful, painful, and above all very human poet to the attention of Anglophone readers.

Hikmet’s life was extraordinarily dramatic. One of Turkey’s most popular poets, he was sentenced in 1938 to twenty-eight years in prison on trumped-up charges of inciting the youth to communism. He served thirteen years, and then spent the rest of his life in peripatetic exile throughout Europe, fearing assassination if he returned to Istanbul, where he had left his wife and family. His escape from Turkey involved a midnight sailboat cruise to Bulgaria, a shipwreck, and rescue by a Romanian freighter. Hikmet climbed a ladder onto the boat and was escorted into the galley, where he found a poster of him with the words “Save Nâzım Hikmet.” This is just one of the numerous legendary incidents in the life of “Turkey’s world poet.”

But readers seeking an impassioned retelling of the poet’s life and times will be disappointed with this biography. The scholarship of Konuk Blasing, who is a professor of English at Brown University, is exemplary, judging from the array of Turkish-language texts on Hikmet she cites. And her interpretations of Hikmet’s poetry, which appear liberally throughout the book, begin from a facility with Turkish that only a native of Istanbul possesses. She has written an informative scholarly biography.

Poet-biography is a genre all its own. The best examples are as creative as they are researched. Richard Holmes’ Shelley: The Pursuit is an astoundingly lyrical narrative of the life of Percy Shelley. Paul Mariani has written dramatically and well on the lives of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Hart Crane, Robert Lowell, and others. In short, there is no reason why a biography cannot — why it should not — combine scholarship with a warm recreation of the subject’s life.

It is true that Hikmet provides a particular challenge to biographers: His post-prison years were certainly adventurous, but his life in prison, if not necessarily boring, forces us to focus almost exclusively on his texts, rather than the events of his life. That is not necessarily a disadvantage, as the poems and plays he wrote in prison are some of his most powerful. One of them, a love poem to his wife, begins:

Over the rooftops of my far-off city

under the Sea of Marmara

and across the fall earth

your voice came

rich and liquid.

For three minutes.

Then the phone went black…

Hikmet’s poetry, in Konuk Blasing’s translations, combine a romantic sensibility with the crushing disappointment of reality. His language is lithe and lyrical, music arising from a keen compression. Combine his lively, alluring voice with the unusual circumstances of his life, and what emerges is a poetry of amazing vitality, the enthusiasm of which, the very composition of which, was a revolutionary act, and a protest against extenuating political and personal circumstances. This direction of Hikmet’s work peaks with “After Getting out of Prison” a four-part poem with the kind of first-hand knowledge we read poetry to encounter:

The air is cool

like baby hands.

You want to hold it in your palms

and warm it up.

The neighborhood cats wait at the butcher’s door,

and upstairs his curly-haired wife

has settled her breasts on the window sill,

watching the evening.

Half-light, spotless sky:

smack in the middle sits the evening star

sparkling like a glass of water.

[…]

Hikmet was not only a prison poet. He was also a dashing love poet, as his “9-10pm Poems” to his second wife show. He was, too, a poet of public responsibility in the same league as Pablo Neruda. In his exile years, Hikmet was active in conferences around Europe, and wrote numerous poems protesting nuclear armament and other modern geopolitical issues. But Hikmet was until the end fascinated with moments when the individual comes into contact — often violently — with authority, as well as with his own past, through memory. Hikmet was a poet of longing, an idealist forced to constantly to question his idealism.

One of his final poems, “Straw-Blond,” written in 1961, imagines meeting himself at 19-years-old, a year that Konuk Blasing describes as particularly significant in Hikmet’s life, when his belief in communism ripened to full maturity, before it was devastated by a visit to Russia, and later revelations of Stalin’s purges. According to Konuk Blasing, “[Hikmet’s] nineteenth year was not only about youth; it marked a magic moment — a sleight of vision — when the poet and the Communist were one. His awareness of the widening gap between these two figures and his determination to keep the two together shaped his work.”

This poem, one of Hikmet’s major late works, gives voice to the poet’s wandering life, and the way his life, and his art, were radically altered by political and personal circumstances.

the clock tower of the Strastnoi Monastery rang midnight

actually both tower and monastery were town down long ago

they’re building the city’s biggest movie house there

that’s where I met my nineteenth year

we recognized each other right away

yet we hadn’t seen each other not even photos

we still recognized each other right away we weren’t surprised we

tried to shake hands

but our hands couldn’t touch forty years of time stood between us

a North Sea frozen and endless

[…]

the world is the taste of a green apple in his mouth

the feel of a fourteen-year-old-girl’s breasts in his hands

songs go for miles and miles in his eyes and death measures a

hand’s span

and he has no idea what all will happen to him

only I know what will happen

because I believed everything he believes

I loved all the women he’ll love

I wrote all the poems he’ll write

I stayed in all the prisons he’ll stay in

I passed through all the cities he will visit

I suffered all his illnesses

I slept all his nights dreamed all his dreams

I lost all that he will lose

her hair straw-blond eyelashes blue

Hikmet’s poetry is filled with clock towers at midnight, first snows, women compared to honey and roses, and other tropes that now seem humorously “romantic.” This is not a term that Hikmet objected to. But for modern readers, a large part of the interest in Hikmet’s work comes from extra-textual circumstances: His imprisonment and exile. Prison was a boon to Hikmet the poet, even as it nearly destroyed Hikmet the man. The austerity of prison life seems to have hardened Hikmet’s sensibility, while preserving the value he placed in human relationships.

The greatest strength of this biography is that Konuk Blasing’s intimate familiarity with Hikmet’s poetry allows her to illuminate the formal revolution that Hikmet led in Turkish poetry. From his step-down lines, which he learned in part from meeting Vladimir Mayakovsky in Russia, to the reinvigoration of ancient Turkish forms, to his later work with syllabics, Hikmet’s poetry challenged his readers formally as it challenged the authorities politically.

As Konuk Blasing points out, the times were right for a Turkish poet to break the mould. Turkey went through a linguistic revolution during Hikmet’s lifetime. The first President of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, decreed in 1928 that Turkish would shift from Arabic script to Roman script, and would be “purified” of foreign vocabulary, essentially forcing the entire nation to relearn its own language. Hikmet was concerned with the politics of language and the politics of communism, and his ground-breaking poetry established him as the leading voice in the new Turkey, and thus a threat to the authorities. While Hikmet’s poetry seems less than revolutionary today, at least for Western readers — most poets wouldn’t dream of being taken so seriously by authorities as to be imprisoned — the elasticity of his voice, and the singular clarity of his vision remain as vital as ever.

There is still no more complete source for Hikmet’s work in English than Konuk Blasing, who is also a noted scholar of American poetry. Hikmet’s poems in her translations with Randy Blasing shine from these pages. Perhaps that is, above all, what readers will take away from this book: Hikmet’s poetry will not be bound by authorities, be they book covers, scholars, or politicians.

–Stephan Delbos