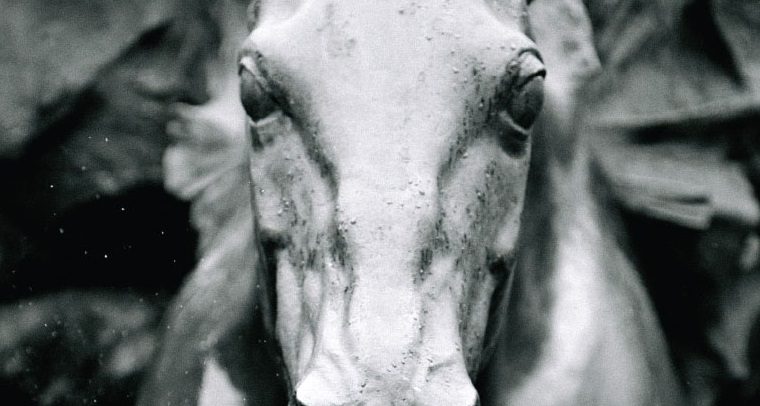

Seven Terrors

by Selvedin Avdić

Translated by Coral Petkovich

Istros Books, 2012

150 pages

To some people the word horror simply denotes a genre, whether an ancient one containing ghosts and demons or a modern one of slashers and sleepover parties gone terribly wrong. To others– people from places like Rwanda, Cambodia and Sarajevo among many other parts of the world – horror probably doesn’t immediately prompt thoughts of fanciful, made-up stories meant to be enjoyed and occasionally even laughed at. It’s an inadequacy of our language that we use the same word to describe entertaining fictions as to describe the murder and inhumanity that darkens real life.

On March 7, 2005 the hero of Selvedin Avdić’s brilliant and captivating novel Seven Terrors decides to get up out of bed after nine months of self-imposed inertia after his wife has left him. Ready to return to life what he actually returns to is horror … horror in both of the above senses, or what might best be described as a place where wartime atrocities and ancient Balkan tales of spirits and demons blend together in a chilling Bosnian concoction.

The very day the narrator arises from his bed he is greeted by Mirna, the daughter of his old friend Aleksa, who has come from Sweden in search of her missing father. In fact, it was her call the night before that had partially prompted him to end his nine-month gestation. Aleksa had mysteriously disappeared during the war in the early 90s. Mirna has brought the notebooks her father had kept as a journalist, and they contain some obscure references to what might have happened to him. This is what brought her back to Bosnia and to her father’s former friend. This is also where the novel enters the underworld, literal and figurative, criminal and supernatural.

The reader is brought back into Aleksa’s thoughts and experiences from the war years by reading what amount to diary entries. He was working on an article about the local mine, and during a trip down with the miners when everything begins crashing around them he recounted seeing an extraordinary vision:

“In the middle of the light stood a tall, thin man in a long green coat, with a large round collar and black buttons as big as a miner’s fist. He had thick, black hair, shining like coal. His face was white, like in a pantomime, his nose narrow, and his eyes did not have any whites, I saw that very well, for they were just little black balls. He bowed to me, and I screamed, because his body broke in half at the height of his chest.”

Aleksa is told he has seen Perkman, a djinn, the sight of which either will lead one to gold or heralds an accident. From then on Aleksa follows two obsessions – seeing Perkman again and being reunited with his wife and daughter, who had gone abroad to escape the war. He even finds the people capable of fulfilling both of these wishes – the Pegasus brothers – two of the most vivid and sinister villains in all of contemporary literature.

Albin and Aldin Pegasus were born a ghostly white, made pariahs by their neighbors for their eerie appearance and thieving tendencies. One day the townspeople ambush them and beat them senseless and the brothers aren’t seen for almost a year. Then, suddenly, they reappear, their formerly white hair now bright red: “That morning the worst criminals in the town’s history were born.”

Avdić creates these two characters that could have come off the pages of Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita yet he never loses sight of the very real moral issues they are involved in. They are stimulating, entertaining villains yet they are also war criminals involved in torture. They are evil.

And it is this proximity to evil, the belief that you can come into contact with it and get away unscathed that is one of the myths this story shatters, and not only for the main characters but for some of the peripheral characters too, whose role in the war ends up being different than you thought at the beginning of the novel.

Ultimately, the mystery of what happened to Aleksa is revealed, yet the lines between the world of fact and world of legends as well as between the kind of horror experienced during the war and the fictional horror that this novel also contains are left undefined. There are some mysteries that aren’t meant to be done away with.

— Michael Stein