The Last Vispo Anthology

The Last Vispo Anthology

Edited by Nico Vassilakis & Crag Hill

Fantagraphics Books

What is poetry? It would seem a strange poetry anthology that sparks such a question, and indeed, by traditional standards, The Last Vispo Anthology is strange. It is also challenging, eclectic, confounding, erudite, punchy, and, by turns, beautiful.

One of the strangest aspects of the anthology is the name of the artistic and literary movement it quite successfully catologues. Visual poetry is visual, and much of it is beautiful, but it isn’t poetry, says the stringent critic. But then, what is poetry? Is its essence in form, or effect? Evidently, The Last Vispo Anthology is also provocative. Not only does the work of many of the writer-artists in this anthology inspire, shock and delight, as do the best of the essays, which are erudite and expansive; the anthology is an interrobang, the punctuation mark combining exclamation point and question mark invented by Martin K. Speckter in 1962, which qualifies as “visual poetry” as clearly as anything included in this book. It’s true though: The Last Vispo Anthology seeks to confront and to challenge, even as it questions its own existence.

Clearly, it is odiously unnecessary to argue against the use of the word “poetry.” But for the sake of consideration: Whether you agree visual poetry is poetry depends on your definition of poetry. Horace said poetry must instruct and delight. Coleridge said the best words in their best order. The most successful visual poetry would perhaps have sat well with Horace. But not Coleridge. It is a question of order. Visual poetry subverts order. It has the immediacy of visual art, whereas text relies on order, which it achieves through linearity. Works in this anthology thrum on the border of visual art and text, a remarkably potent place to set up camp. They achieve the best of both worlds, combining writing and visual art; order (and thus surprise), and immediacy (and thus contemplation).

The metaphor of setting up camp is apt, for, despite the size of the book, the number of poets included, and the variety of the pieces, the volume retains the feel of a camp, as if visual poets were constantly aware they were in the minority of the minority of poets and artists. The essays in particular draw out this theme. But first, the art/poetry! The anthology has been deftly divided in four sections: Lettering, Object, Typography, and Collage, categories that speak to the diversity of the work included.

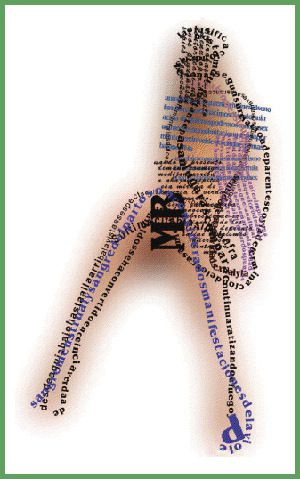

Some of the pieces, like Miguel Jimenez’s Presences 5c, of the series Presences, show the inspiration of literary predecessors, specifically Apollinaire, whose posthumous publication Calligrammes (1918) was one of the early sustained efforts to explore the written word as picture in European or American poetry. But Jimenez has modernized this influence, with a warm flush of color, and fonts that make the piece multi-layered and lush.

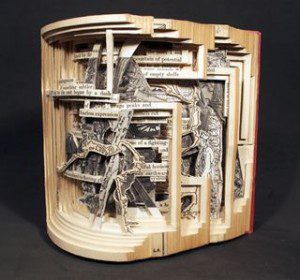

But most of the pieces here are far less indebted to poetry — or even the written word — than to visual art. Troy Lloyd’s Untitled, for example, is more about texture and chiaroscuro than language. But that is not true for all the artist/writers here. Oded Ezer’s The Message, for example, uses the depth of photography combined with the tactile texture of paper to add multiple dimensions. The book sculptures of Brian Dettner are particularly intriguing, and seem to take the work of Joseph Cornell into another dimension, and one that is more austere, more textual, less uncanny, but equally haunting.

But The Last Vispo Anthology is not just about the work of artists. There are numerous essays on visual poetry included here, from critics and practitioners of the art. This is an anthology with a critical clarity that endeavors to present visual poetry with full knowledge of this particular moment in the movement’s history. There is an ample serving of critical essays and observances. Editor Craig Hill even provides a guide to reading visual poetry that will no doubt be handy for the neophyte:

Reading a visual poem takes a minimum of three steps (pour over the following essays for additional ways of making meaning from visual poems): 1) Read the entire page/space at once. The visual poem is designed to first be read whole (unlike most poems on the page chained to left to right, top to bottom regimens). 2) Read the parts of the whole. Consider their position on the page/in space, their relationship/s to other parts. Much that happens in a visual poem happens here. 3) Read the full poem again at the same time reading its elements as they combine and re-combine to create the whole.

Some of the prose pieces are as vibrant as the visual poetry included here, which is no mean feat. But there is also some important critical insight, especially Donato Mancini’s essay “The Young Hate Us {1}: Can Poetry Matter?” which provides a clear and concise history of the page, and thus shows essentially how visual poetry has got to where it is. Bill Marsh’s “Visual Education” is another eloquent essay, and one that underlines a desire the whole anthology expresses, which is the desire of visual poetry to confront itself. This is at least partially the work of a movement that knows the powers, and, often, the necessity, of self-documentation.

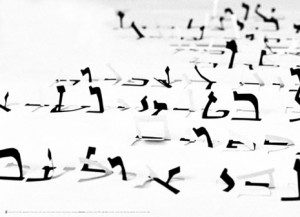

Karl Young’s essay “A Sphere and a Line” is particularly erudite, and it makes one consider how many avant-garde literary movements have had a built-in critical apparatus, a group of learned apologists who were also practitioners of the art. In the best sense, a critic can ease the transition between writer and reader, but such a collection of essays as is included here can seem to belabour the point, which is that visual poets migrated away from the strictures of the line into the open field of the page, and then further into a focus on the letter as object. As Young writes, “At present, those who identify themselves as poets have nothing in common but history.”

But overall there is an elegiac note to this anthology, which extends from the title to the feeling, put forth by several of the essays, that visual poetry is facing a turning point. With more readily available technological advances at their fingertips, many visual poets are veering into visual art, seemingly leaving the roots of the movement behind. Karl Kempton writes that visual poetry will soon be over, while Jim Leftwich writes that the movement is still gaining adherents. A contradiction? Perhaps. But then again, these essays are not without their questionable assertions. Mancini, for example, writes “A modest to high degree of vagueness serves poetics.” Really? It is an assertion that points to the distance between visual poetry and, well, poetry.

Visual poetry is not poetry. It is visual art that uses words. To trace its arc means to go back to the days, of Horace and others, when poetry was dictated, not written. Then the shift toward print began and orality was in large part, in western poetry, not awakened again until the 20th century, when at the same time, a greater interest in the technology and possibilities of page itself became evident. Visual poets are continuing the swing of that pendulum. But one can’t escape the feeling, reading this anthology, that visual poets are poised on the apex of the pendulum’s swing, or at least believe they are.

In the 21st century, when daily existence brings us into contact with hundreds of works of media each day, many of which blur the traditional boundaries between genres, in effect accomplishing the same feat that once seemed so unique to visual poetry, the term “visual poetry” seems defunct. And yet, this work is distinct. Lusher and more complex than the minimalism pioneered by Aram Saroyan and others in the 1960s, divorced from the text-based practices of language poetry, more insistently authorial than flarf, and concerned with the visual physicality of letters, rather than the heft of language conceptual writing aspires to, visual poetry is the bastard hermaphrodite of arts and letters. In a good way.

—Stephan Delbos